Interview by Brad Walseth

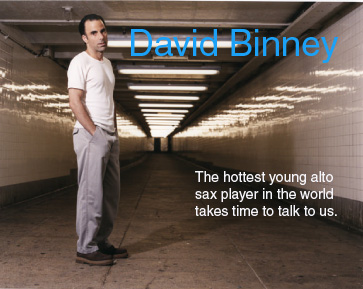

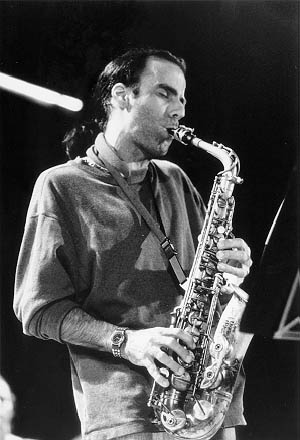

JazzChicago’s 2006 Artist of the Year was alto saxophonist David Binney, who released not one, but two of our favorite recordings of the year – “Cities and Desire” and “Out of Airplanes.” Earlier this year Binney and frequent collaborator Edward Simon released the fine “Oceanos,” while the new Donny McCaslin recording “ In Pursuit” — which was produced by Binney and also features some of his incendiary playing, recently came into our hands and is a knock-out and nearly assured to make our top-10 list for 2007. A renaissance man who composes, produces, and plays some of the most dynamic alto sax you’ll hear, Binney kindly took time from his busy schedule to talk to us about the past, present and future of one of the world’s most exciting jazz artists. Ever humble, Binney neglected to mention he had recently been voted the #1 Rising Star on Alto in Downbeat Magazine, an honor for which he is most deserving.

JC: How are you today?

DB: Good, good. I stayed up really late writing big band charts, believe it or not, so I just started my day about an hour ago.

JC: Who are you writing big band charts for?

DB: For myself. I got commissioned by the Jazz Gallery here to do these big band concerts. I was supposed to do them actually in March or May, I can’t remember, but there was no way I could get it together by then because I had never written big band charts. I was traveling a lot, and then I moved it to August, but I was traveling half the summer and I couldn’t get it together, so now I moved it to November. I’ve been writing these charts and I’ve got four of them done and I’m going to do another four and try to do these concerts — maybe a recording — it’s pretty crazy.

JC: When are you doing the concerts – November?

DB: November, I can’t remember the exact dates – I’ve got them written on the calendar– the 7th or 8th or something.

JC: Well that’s something exciting – something new that you haven’t done before?

DB: Yeah, completely different. I had no idea when I first started. I mean I played in big bands all my life, but I never wrote anything for them. So, plus I had to learn Sibelius (music software), which is a program I didn’t know. And that’s a pretty complicated program. The combination of writing all this new stuff and learning the program was a little daunting, but somehow I’ve managed to do it. I don’t know – these charts they could be good, I just haven’t played them with anybody yet, so we’ll see.

JC: 2006 must have been an emotional roller coaster of unbelievable proportions, can you talk a bit about what you experienced?

DB: Do you mean in my music or my personal life?

JC: Both – you put out the two incredible records, but you had some things in your personal life like the death of your mother.

DB: My mother actually… it was two years ago in August — technically 2005. So yes, 2005 was pretty crazy. 2006 was not such an emotional roller coaster, but was very busy with a lot of stuff going on. And yeah, just when there’s a lot of stuff to be done or you accomplished a lot it’s hard to even go back because it’s just a blur in my head. So excuse me if I’m not real clear about it. I traveled a lot, toured a lot, and then within that got all these records together, some of those dating back really to 2005. “Cities and Desire,” I did in 2006, but “Out of Airplanes” in 2005, as was “Oceanos” –— so I think that was the year that was the crazy one. I think 2006 was for me, more of stuff coming out and dealing with that, and a lot of roads and people.

So 2005 I think was probably the more emotional time. That was tough because I was trying to get all of this stuff together and at the same time take care of my mother and tour. At a certain point my mother was really bad – I would leave Europe and come back to California actually even for days at a time, then go back to Europe to continue touring – then come back – back and forth – which is a long way. Obviously, not even like coming back to NY — it’s a lot further – so I was dead and completely out of it.

JC: So it was the opposite of Out of Airplanes — you were actually spending lots of time in airplanes?

DB: (Laughing) Yeah – that was the whole thing. I think that’s why I thought of that title, because I was in airplanes so much, and I was taking these pictures out of the airplanes –— taking these pictures from the air. I started doing that on every flight, when we would take off and land, and at different points on the flight — because I was traveling so much.

JC: Well “Out of Airplanes” was a bit of an unusual session for you, featuring Bill Frisell, that seemed to really come together so well — what was that session like? How did that come about?

JC: Well “Out of Airplanes” was a bit of an unusual session for you, featuring Bill Frisell, that seemed to really come together so well — what was that session like? How did that come about?

DB: Well, even that was really kind of difficult, because I hardly ever get sick. But those two days I got really sick – I had a 103-degree fever those two days we were in the studio in Seattle. And at one point, I even remember kind of hallucinating in the studio, because I was so feverish. It was really pretty difficult session. It was good – I liked it, I definitely liked it, but it was hard for me to get through it.

JC: I think there’s a photo on your website from that session where you’re wearing a stocking cap in the studio while you are playing.

DB: Yeah, you know that thing when you get feverish? I was shivering. Plus, it was Seattle, so it was cold. But yeah I was really out of it. Anyway, that session came about because Kenny Wolleson — who’s one of my best friends, and lives right upstairs from me – and we were just talking about doing something over the years. I mean we have done a lot of stuff together, but I’d always wanted to record with Kenny and had never done it. So I started to imagine a project that we could do. Then Kenny and Taborn and Eivind (Opsvik) and I did a gig out in Williamsburg one night, and it was really good. It was really great, and I decided to make that the project. And I thought I‘ve always wanted to do something with Bill. So I saw those guys – Kenny and Bill, at the Vanguard one night, and I asked Bill if he’d be into it, and he said‘yeah.’

And then his schedule was so crazy, that I thought maybe it would be easier if we went to Seattle when he’s there to record, because he’s always traveling. And it would be good for me, because I’m always recording at this studio in Brooklyn and it would be nice to do something somewhere else. So Bill has this studio he loves — the guy there gets his guitar sounds so we went out there. And it was actually really cool, because it was nice to record somewhere else, and get a completely different vibe for that project. It was good too, because I wanted a different sound.

JC: It is really different. Your playing on “Out of Airplanes” is so restrained and kind of austere, while “Cities of Desire” features some of the most emotionally intense playing I’ve ever heard on record — was this record a catharsis of sorts?

DB: Well, I think I think of those – because of the nature of the company – Criss Cross, it’s more like a “blowing record” sort of company. We don’t have that much money, so people go in and make whole records in 6 hours. I mean Cities of Desire was made in 6 hours.

JC: That’s amazing.

DB: We just went in and played. I mean that is the working band, so we just — all we had to do was go in and play. We played three tunes at a time, without any break. and that’s how I put the record together. And I think we did everything is first take, except for the first three tunes, which I think we did a couple of times But the rest we did was all first take stuff. We just went in and played and that was it.

That’s how a lot of those Criss Cross records are made. I just wanted to capture the band somewhat as we are live for those records, because that’s the company to do that with. For our own record label we had a couple days, and I wanted to make it a lot less of a blowing record and more of a… My idea was to do a lot of free improvisation and then work on it after the facts at home. But we actually just played. There’s really very little of what I originally intended to do, because I can’t help writing, so I wrote. A lot of what you hear there is just what happened in the studio. And then there are those little shorter pieces that — a lot of which Eivind sort of manipulated later. I manipulated some of it to make these little pieces/vignettes and stuff, but basically it’s a live record, where I didn’t feel like playing a lot, that wasn’t my concept for this record, personally… and having the 103 fever was a little hard for to really stretch anyway.

That’s how a lot of those Criss Cross records are made. I just wanted to capture the band somewhat as we are live for those records, because that’s the company to do that with. For our own record label we had a couple days, and I wanted to make it a lot less of a blowing record and more of a… My idea was to do a lot of free improvisation and then work on it after the facts at home. But we actually just played. There’s really very little of what I originally intended to do, because I can’t help writing, so I wrote. A lot of what you hear there is just what happened in the studio. And then there are those little shorter pieces that — a lot of which Eivind sort of manipulated later. I manipulated some of it to make these little pieces/vignettes and stuff, but basically it’s a live record, where I didn’t feel like playing a lot, that wasn’t my concept for this record, personally… and having the 103 fever was a little hard for to really stretch anyway.

So my whole thing was to let Bill go and let the groove develop. I’m really happy with the record. I’ve done two very electric records under my own name — this and “Balance,” and I found with both of those records there’s a certain crowd that absolutely loves them, and then there’s a certain crowd that gets really confused. They hear me do something on CrissCross, and it’s a blowing record and I’m playing “Lester Left Town” or “Heaven,” or something, and then the next thing is kind of funk/electronic thing, and they don’t know how to deal with that — it’s confusing. I don’t think a lot of people reach for those extremes.

JC: I think it shows breadth in your interests in your abilities. But, I know what you mean — many people would like to pigeonhole an artist into a particular genre.

DB: I think people get confused. There’s a lot of subtle stuff in that record and they don’t really get that as much. It’s not as obvious as “Cities and Desire” which is traditional format. There’s a lot of subtlety in “Out of Airplanes” that I really like — a lot of time spent on little sounds and stuff, and I don’t think reviewers get a lot of that at times.

JC: I want to question you a bit about your writing style — do you write from the keyboard?

DB: Yeah, that’s how I write — from the keyboard. To be honest with you, I don’t really know the keyboard. Years ago, I took piano lessons a little bit, but I couldn’t sit down and you put a chart in front of my face, and then I’d play the tune… I couldn’t do that. I know what the notes are, but that’s not how I write. I write what I hear, and I’m very good at putting my hands on the keyboard and coming up with something. The minute I hear something, when I place my hands on the keyboard, it starts to develop. I just take it to its logical next step. I don’t think about anything else. I don’t think about what key it’s in, what the chord changes are, anything — I just take it melodically to its next place.

That’s the way I write. And I think its funny, because I’ll get students who’ll ask about writing, and I’ll show them how I do it, and they’re surprised, because they’re so stuck in — “this chord going to this chord.” I tell them, I just write what I’m hearing, and later on I figure out what time signature it’s in. The chord changes I figure out very late, if I ever figure them out at all. A lot of times I just write the chords out like in classical music, and once in a while, if we blow on a lot of changes, I’ll have the keyboard player or guitar player figure out what the changes are. Because, I realize what I’ll call chord changes a lot of time, people who play a chordal instrument will call it something else. When I go to rehearsal, I’ll just give the thing to Craig (Taborn) or Jacob Sacks or Adam Rogers and ask them to figure out what the changes are. And they’ll come up in five minutes, and write down some changes, and that’s what we’ll use. Then I know it’s going to work, because that’s the way they see it. It works best that way for me.

That’s the way I do it. Writing is from a pure slice of… just really organic. I think it works in my favor. It comes also out of being naďve about the keyboard. I studied. I know harmony and could figure out everything in my own way. I know how to do that. Sometimes people say — ‘oh you’re just writing by ear.’ That’s not the case at all, I just don’t get bogged down by a lot of rules. I didn’t go to music school. I mean I did when I was very young, but I chose not to after high school, and one of the reasons why was because everyone I heard that went to music school sounded like they went to music school. I studied privately and developed my own thing. I never memorized solos. I never transcribed, which is really unusual in the jazz world. I listened probably more than anybody. I listened to everything. I still do. But, I didn’t literally take stuff from other people and memorize it, because, I felt like — ‘why do that?’ I mean I did play a lot of classical music and then learned all the harmonies for jazz — and if you put those two things together, technique and the knowledge of harmony, you come up with your own stuff anyway. That’s been my whole theory and it works and is true for composing also.

JC: On a bit of a different note, like with Edward Simon, you seem to have a kindred spirit with Donny McCaslin. How did you hook up with him and get the producer gig?

JC: On a bit of a different note, like with Edward Simon, you seem to have a kindred spirit with Donny McCaslin. How did you hook up with him and get the producer gig?

DB: Well there again, there’s a certain circle. A lot of the people you see on my records — they’re not only just the guys I use, they’re like my family. We’re really close. Me and Donnie McCaslin and Scott Colley and Adam Rogers have been friends for years — I mean really close friends, and have done so many gigs and have done so many projects together. And in the last seven or eight years, it’s been the younger guys like Thomas Morgan and Dan Weiss and Taborn and Chris Potter. All of us are such super good friends to begin with — we’re always together hanging out talking about projects and things anyway. So with Donny — we’ve had (conversations) for years and from playing on each other’s projects. He likes the ideas I have about music. A lot of times in the studio I’ve been the one to come up –—‘why don’t we do this,’ or ‘let’s cut this section out of this tune’ — so people started to realize I could produce stuff.

I produced the last Scott Colley record too, even though it doesn’t really say that. It lists me as producer, but equally with this other guy Ermanno Basso and with Scott. In reality I was the one who produced the whole thing — so it wasn’t actually Scott’s fault. It was the company — they didn’t really give me the credit for it, but it’s just something that’s really natural for me. So I’ve always helped Donny with his compositions and stuff, even before I started producing him. But he’s doing a trio record soon and I’m helping a lot with the compositions on that. Not that I’m producing, because it’s only a trio record, and I don’t think he needs that. But he’s always consulting with me about that stuff. And it’s great — he gives me a lot of leeway, and I can really go with it. I’m there for every process of it including the mastering.

JC: One thing that really stands out about the new McCaslin album and “Cities” is that there is a palpable excitement in the playing of the players — there is so much life and excitement in the playing. I hear albums all the time that are well recorded and well played by top flight musicians, but there is a certain something in your recordings that really seems to take it up a notch to a higher level or into a new dimension — the music sounds multi-dimensional. Is this a production technique, the players or the compositions, or a combination, because I’m sure there are quite a few producers out there that would love to know your secret?

DB: I think it’s a combination of all. I mean, Donny is a great player and a great composer, and all those guys on the record are great. And they’re excited to be playing a record like that because it’s a fun thing to do. And I think we spent a lot of time in the production phase of it too, so I think that that all comes across. You know Donny — I think we make strong records together, and I hope he keeps doing it that way. I’m sure he’ll probably record another one for Sunnyside at some point — maybe next year. And we’ll see what happens. I know we’re doing some gigs next year. We’ve done some gigs with that project — we were just in Portugal for a week, and I don’t know about later this year, but we’re doing some stuff next year, because he just emailed me even about next July 4th and 5th, if I remember correctly, in Europe. So, he’s keeping this project together, and I think hopefully he’ll record some other stuff.

DB: I think it’s a combination of all. I mean, Donny is a great player and a great composer, and all those guys on the record are great. And they’re excited to be playing a record like that because it’s a fun thing to do. And I think we spent a lot of time in the production phase of it too, so I think that that all comes across. You know Donny — I think we make strong records together, and I hope he keeps doing it that way. I’m sure he’ll probably record another one for Sunnyside at some point — maybe next year. And we’ll see what happens. I know we’re doing some gigs next year. We’ve done some gigs with that project — we were just in Portugal for a week, and I don’t know about later this year, but we’re doing some stuff next year, because he just emailed me even about next July 4th and 5th, if I remember correctly, in Europe. So, he’s keeping this project together, and I think hopefully he’ll record some other stuff.

Now my interest — unbeknownst to him is — I think if he does another record for Sunnyside, I would suggest going in even… taking it in a different direction. Because we’ve sort of explored the Latin thing the last two records. The one before is one of the records I love — “Soar.” If you like this record, get Soar because that record, the way that came out, I really love. I love both of these records, but I really love that record. And that got a lot of attention last year. So we’ve done two, and we’ve sort of stayed in this kind of Latin jazzy vein. I kind of even put it in more in the Latin jazz direction in this latest one, because Donny is really strong at playing in that thing — the 12/8, 6/8 sort of feel. Stronger than anyone I’ve heard — especially on saxophone — so I tried to exploit that a little bit. But we did that also on the last one, and I think if this continues next year ,we’ll try to be a little different.

JC: What’s your opinion of your alto playing on the record?

DB: Well, it’s not like I’ve listened to it a lot after I’ve done it, but… There was some student who came to me that loved one of the solos on that record that I took and wanted to ask about it, so I had to go back and listen to the stuff recently. And yeah, I actually liked it, and I thought ‘yeah, that was good.’ You know how it is, you play the stuff and then you pick the takes and you sort of live with what you’ve done. Sometimes you’ll take the takes and edit — if somebody takes a solo you’ll edit from one take to another. I think we might have done that once on Donny’s record, although it’s pretty much just like what it was recorded, but yeah I think it’s good. I felt good. But it’s funny because you develop so much that already feel like such a different player than I did even then, because I’ve practiced and played so much since then.

JC: Do you get the sense you are breaking new ground? It seems like every time I hear you, you are getting better and better.

DB: Well, I feel that way, as is Donny. We work hard. Actually everybody, especially the saxophone players I hear lately. Everyone I play with — I can’t think of anyone I hear who doesn’t sound like their actually improving all the time. And that can be a scary thing because like Chris Potter — he’s ridiculous. And the other night I went and hung out at Antonio Sanchez’s gig, and Chris was playing with Miguel (Zenon) & Scott and Chris was just ridiculous. It was even a new level for Chris, and I realized ‘wow, everybody’s just developing.’

Tonight I have a gig with Miguel and we’re playing with this guy, Miles Okazaki. He just got the Doris Duke grant to tour and record another record next year and that’s with Dan Weiss — he’s the drummer in my band and a bass player named John Flaugher and – it’s me and Miguel Zenon and this guy Christof Knoche, and Miles Okazaki plays guitar and he made a really, really interesting record last year. It’s actually gotten some good attention. It’s gotten good reviews in all the magazines, and now he’s won this grant and he’s getting attention for the music. It’s very difficult music, really hard music, but fun, and really fun to play with Miguel in this group – we have a good rapport. Miles Okazaki –—“Mirror.” It came out earlier this year — February or March. Okazaki is a really cool composer and a great guy. He plays guitar — his main gig is with Jane Monheit — which is completely different from what you’d hear on his records. Chris Potter is also on his record, playing on one track –— a really cool track that they basically improvise over “Satellite” or “26-2” or one of those Coltrane tunes with some electronic sound. It’s really a very interesting thing. Pick that record up. That’s another young guy who… especially as a composer, he’s going to be important among the younger guys on the scene.

Tonight I have a gig with Miguel and we’re playing with this guy, Miles Okazaki. He just got the Doris Duke grant to tour and record another record next year and that’s with Dan Weiss — he’s the drummer in my band and a bass player named John Flaugher and – it’s me and Miguel Zenon and this guy Christof Knoche, and Miles Okazaki plays guitar and he made a really, really interesting record last year. It’s actually gotten some good attention. It’s gotten good reviews in all the magazines, and now he’s won this grant and he’s getting attention for the music. It’s very difficult music, really hard music, but fun, and really fun to play with Miguel in this group – we have a good rapport. Miles Okazaki –—“Mirror.” It came out earlier this year — February or March. Okazaki is a really cool composer and a great guy. He plays guitar — his main gig is with Jane Monheit — which is completely different from what you’d hear on his records. Chris Potter is also on his record, playing on one track –— a really cool track that they basically improvise over “Satellite” or “26-2” or one of those Coltrane tunes with some electronic sound. It’s really a very interesting thing. Pick that record up. That’s another young guy who… especially as a composer, he’s going to be important among the younger guys on the scene.

JC: You’ve been one of the relatively few jazz artists to really utilize the Internet fully, for example: offering downloads of your gigs for sale online — can you talk a bit about your thoughts on new technology? I was talking to a sax player the other night in a club ,and he was upset about all the downloading going and doesn’t know how he’s going to make a living. You seem to understand the problem, but are finding ways of getting around it or ways to work within it even.

DB: Well downloading was initially a problem. And then at a certain point it went way beyond being a problem — it was just a reality that we have to deal with, because it’s not going away. There’s no way around it. People are just going to trade more and more. Music has basically become free. People still sell cds and that, but there’s no record stores to sell them in — all the stores went out of business. So, its either on the internet, where I sell a lot of çds, or the other way is just to play live. Really the way to make a living is just to play live and sell your cds on the road — which you still do sell cds on the road. Selling them from the bandstand or a desk or something. People will buy a lot of them. But even then, I’m going to offer selling downloads, because first of all I don’t want to carry cds with me on the road, and second of all I think people are getting more and more used to downloads, and people buy the gigs as well.

You know the thing you have to remember — when people say ‘I don’t know how I’m going to make a living’… I don’t know who this saxophone player is, but you ask that saxophone player or anybody — did they ever get any money from the records that they made anyway? And I guarantee everybody will say, ‘well no.’ So what’s the difference? It’s actually a great time for music and musicians, because we’re in control of the content on the records, and we’re in control of where we advertise it. We have total control of that. When I come out with a record on my own label, or even on another, I hire my press guy, Chris (DiGirolamo of TwoShow Media) to work it, and he gets it to all you guys and it gets out there. That’s more than most any label I’ve ever been on has done. Even Criss Cross, they don’t get the record to you. The only reason you get that record is because I give it to Chris. I hire Chris to do it. Otherwise you’d never know about that record, unless you were totally following Criss Cross.

So what good is Criss Cross doing for me other than financing the fact that I’m going into the studio? That’s all it is, they’re paying the guys for that. I’m not making any money from Criss Cross. The only thing I make money from is playing live on those records. I’m not making anything from Criss Cross, I’m not making anything from Act Records. I’m not making anything from any label I’ve ever been on, other than maybe a small fee on the day we recorded. But, usually I put that back into the record in someway, like hiring some P.R. guy or something. I don’t know anyone who has made money off a record unless they were on a big label, and then they probably made two records and got dropped anyway. That was a big blow to their career. So, that’s really a poor argument to say —‘how am I going to make a living?’

The hardest thing to do is to make enough money to finance your record, because that’s the thing labels provided before. Now, they don‘t want to give you any money. All those small labels like Fresh Sounds — the artists are paying to record their own record, and then they are giving it to Fresh Sounds or one of those small labels. And then those labels as compensation are giving the person maybe 200 cds so they can sell them at their gigs. So then they end up making 2 grand because they sell 200 cds at $10. And that’s it. It’s still not enough money to pay for the thing. So labels are not really doing anything. You might as well just do it yourself and get it out there. My records — “Welcome to Life” and “Out of Airplanes” saw as much press, if not more, than any of my most recent label records. So what’s the difference? And I own everything.

The hardest thing to do is to make enough money to finance your record, because that’s the thing labels provided before. Now, they don‘t want to give you any money. All those small labels like Fresh Sounds — the artists are paying to record their own record, and then they are giving it to Fresh Sounds or one of those small labels. And then those labels as compensation are giving the person maybe 200 cds so they can sell them at their gigs. So then they end up making 2 grand because they sell 200 cds at $10. And that’s it. It’s still not enough money to pay for the thing. So labels are not really doing anything. You might as well just do it yourself and get it out there. My records — “Welcome to Life” and “Out of Airplanes” saw as much press, if not more, than any of my most recent label records. So what’s the difference? And I own everything.

So it’s actually a good time for musicians. It is hard when you’re a young musician who’s just coming up. It’s hard to see how you are going to make a living. But I think people don’t realize that musicians weren’t making a living doing that anyway. They’ve always made a living off of touring and sideman gigs. That’s the biggest change. Especially for a saxophone player — there are not enough sideman gigs anymore. So you have to do stuff on your own. You’re not getting hired by a quintet or big band —

JC: Not until you bring back the big band sound with your new compositions.

DB: Exactly. Well actually the big band is back — it’s just there’s not many big bands that I like. But, there are a hell of a lot of big bands now. It’s amazing just how popular they are. The schools — the education thing is so big now – that every school has a big band. One of the reasons I wrote the big band arrangements is because Chris Potter and I had this conversation a couple years ago. He had all these requests from universities for big band charts, and he didn’t have any. And I get requests all the time from universities — so I thought I should really buckle down. Chris said this a couple years ago, and he did it, and he wrote about 10 big band charts and he sold them to a lot of schools, and then he gets hired as a package to bring charts to some school, and then play the concert and maybe teach for a couple days. It’s good money. It’s an economic thing. I thought maybe this was a good thing to do. Once I have these charts, it opens up a whole new economy for me. These are all things — getting back to the internet — that you can do as an artist to make a living. I’m making more of a living now than I was a few years ago when record labels were still going. So I don’t buy that argument for a second that labels were ever that important.

JC: Shifting gears here, you’ve made no secret of your love of 1970’s music, including pop and rock classics (and personal favorites of my own) like Rickie Lee Jones’ “Pirates,” Joni Mitchell’s “The Hissing of Summer Lawns,” and Gentle Giant’s “The Power and the Glory,” yet you also are open to current groups like The Shins and The Arcade Fire. That combined with a study of Indian music and an encyclopedic command of jazz, I believe really has contributed to your distinct sound — do you think that’s the case?

DB: I think that that’s a huge part of it. And when I teach and talk to students I tell them one of the best things you can do is be very open and to listen to as much music as possible. And I tell them not just jazz — listen to everything. If you sat here while I’m working during the day I go from Stravinsky in one second, the next second it’s The Shins, the next it may be like Lee Konitz, some ’70s funk thing or some Rhianna. or top-40. I listen to everything and it all feeds into the palette that you have to draw from. I think you need that to — especially with what I do (going to) certain extremes — you have to have a knowledge of these different kinds of things that are going on.

Plus, I just love listening. I love music and all kinds of music. There’s no one kind of music I could say is my favorite kind of music. I could be categorized as jazz, because I play saxophone, and that’s what I’ve presented mainly because I play saxophone and that’s how that is taken. But in the future, I think there will be projects that people won’t categorize as jazz at all. I’ve written a lot of songs that I will probably at some point produce as an electronic record or more of a rock, pop/rock thing with vocals. I’ll do that at some time in the next couple years also. And then people will be really confused.

JC: While I can understand people wanting to be really focused on their craft, but I have never understood why someone would want to limit themselves. You were talking about the palette — why would you limit yourself to just black and white? Unless you are a black and white photographer.

JC: While I can understand people wanting to be really focused on their craft, but I have never understood why someone would want to limit themselves. You were talking about the palette — why would you limit yourself to just black and white? Unless you are a black and white photographer.

DB: Well I limit myself in other ways. I just play alto saxophone. I used to play all the woodwinds. I gave all that up to just play alto sax. Once in a great while I’ll play soprano. I’m very focused. I think that’s a fallacy as well, that you can’t go in between what people think of as different styles and not have a complete focus. Because I think when I’m going between these different styles, I’m really feeling the exact same way as an artist. It’s still coming out in the same emotions, it doesn’t feel different to me. It’s only different in its aural spectrum.

I think it’s all drawing from the same stuff, and it’s all the same thing. And that’s another fallacy — there’s no reason why somebody can’t express themselves with different sounds and be just as honest and just as good at it. I feel that all those records that I’ve done are strong and if I were to do something more extreme, it’ll be just as strong. I wouldn’t put anything out if I didn’t feel it was really strong, so for anyone to say it’s too wide ranging… well I don’t get that.

JC: I know you’re a fan of Sonny Rollins’ classic - “The Bridge” (the first jazz album I ever owned) — and I understand you’ve been playing with guitarist Jim Hall recently – what has that been like?

DB: Well not recently, I haven’t played with Jim in three or four years. But last year Chris Potter, Joe Lovano and I all sat in with him at the Vanguard.

JC: That had to something!

DB: It was really fun. It was Jim’s birthday, and we sort of surprised him. I’m not playing with Jim much anymore — he’s not using saxophone players, or he’s not really playing much because he’s semi-retired — but I talk to him once in a while, and I see him once in a while. But anyway, we went down to the Vanguard one night and I think it was a Sunday night, last set sort of thing. We were all sitting there with our horns and Joe was like —‘I’m going to go and sit in,” and he just walked up and started playing. And Chris and I were like —‘I don’t know,’ we were kind of embarrassed even though Chris has played with him for years, and I toured with him and played a week at the Vanguard with him. But we still felt kind of shy. Finally it was like —‘man, let’s just go up there — it’s his birthday – he’ll be happy — Jim will be happy.’ So we just did. We went up, and we played “St. Thomas” — which was a thrill to play that at the Vanguard with Jim and Joe.

And we played that, and we played one other tune — maybe a blues or one of Jim’s tunes. But it was a blast. We had so much fun, and the audience was just freaking out. There were a lot of students and they had no idea, because it was just spontaneous. And Jim — the major thing was he had no idea we were even in the house, and we all just walked up and played. He actually came back and told us that was one of the greatest days of his life. He was really moved, and it was amazing. But Jim, he’s just one of the great musicians ever and I was lucky enough that he called me to do the Vanguard with him for a week and then we did a European tour with Terry Clarke and George Mraz, with a small string orchestra which was really great. There is one recording — I think the one in Vienna we recorded – it’s recorded really well. I don’t know if he’s ever going to release it. It’s really nice. It’s that quartet with a string orchestra. I hope he releases it. He’s just an amazing musician and one of my all-time favorites.

JC: So what do you have planned for the future? Are you going back to Europe?

DB: Yeah, I’m going back on October 1 for a few weeks with Vinicius Cantuaria. He is a Brazilian singer songwriter who was the drummer in Caetano Veloso band for 10 years. Brazilian music has been really important for me. I was into Brazilian music at a young age.

But the first two weeks — that music is Brazilian. It’s like Caitano Veloso “Livro” – one of my all time favorite records — especially as a producer. But Vinicius is on a lot of Caitano’s releases and he’s a Brazilian singer songwriter. He also plays on “The Intercontinentals” — Bill Frisell’s band. He’s just a great singer, very popular actually. And so it’s kind of interesting. I don’t play very much, but I play — it’s like modern bossa, and I play some electronics. But we go to Europe for a couple weeks, and then I go with — technically it’s under Ed Simon’s name with Scott Colley and Antonio Sanchez ,and it’s the music from “Oceanos.” We are touring under Ed’s name, because next year I’m touring with my band, and it just gives the booking agent — it gives us twice as many possibilities to work. Next year I’ve got more stuff going on.

JC: Any more recordings?

JC: Any more recordings?

DB: Well, that’s being worked on. I did this concert in with the quartet recently — with Brian Blade, Scott Colley and Craig Taborn, and it was really successful, and I realized I wanted to record that group as a quartet. And maybe with the addition of — I did a concert recently in Rome with (guitarist) Kurt Rosenwinkel — and maybe adding Kurt to some of it. Now I’ve talked to everyone about it and everybody’s able to do it in October because Brian’s here and everyone’s going to be around. But I can’t nail Brian down schedulewise as far as dates yet. So even though everyone wants to do it, including Brian, I haven’t been able to schedule it. So I don’t know if that’ll happen. If it does, we will record in October with that band, and then tour a lot next year.

JC: You’re coming to Chicago I hope.

DB: You know I get emails. But Chicago is one of the places where people there don’t seem very interested. Everywhere is easy, but Chicago they always say they’re booked – there’s never any interest (on the part of club owners).

JC: You’re not the only person I’ve heard that from.

DB: It’s really weird. I’d like to play there. And there are a lot of people there like students and such that would like me to come. I’ll see. I could do it, I think, but it’ll take some work.

JC: Well, are you are still holding court down at the 55 Bar?

DB: Yeah, we’re still doing that. We’ve had a couple of really great gigs the last few weeks. That’ll continue.

JC: That sounds like the place to catch the hottest jazz in NYC.

DB: There’s some great stuff happening there. And I do this thing the first weekend of every September. For the last seven years I’ve done that Welcome to Life band. We do it live. And it’s a whole scene. Every set there is sold out. We do three sets a night and it’s lined up 7th Ave and it’s just amazing. People come from everywhere. But were doing that the 6th, 7th, 8th & 9th. Brian (Blade), Chris (Taborn), Scott (Colley) Craig (Taborn)and Adam Rogers and its just super fun. And we all schedule it. Even with everyone’s busy schedules, we schedule it a year in advance, and everyone sticks to it for seven years in a row.

JC: Wish I could be there for one of those gigs! Is there anything else you’d like to add in closing?

DB: I think the biggest thing for me is to mention how important websites are to musicians nowadays. And that people need to support artists through their sites, because the record thing is gone and the Internet thing can develop a lot more than it has. It needs people to embrace it to an extent. Some people are still resistant to it.

|